In the second half of the 17th century, white porcelain painted with overglaze enamel began to be produced at Nangawara in Arita. This pottery, which features elegant designs in fresh pigments painted upon a skillfully created milky white background, was acclaimed not only in Japan, but also in Europe and the rest of the world. Today, this is called “Kakiemon-style porcelain” or simply “Kakiemon.” The name “Kakiemon” refers to the originator of this style, and the highest quality works have been produced in the Kakiemon kiln under the direction of men named Sakaida Kakiemon.

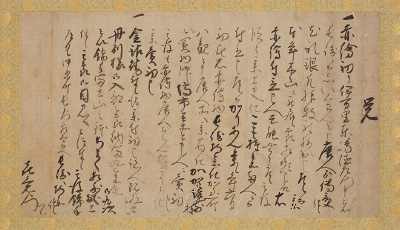

The fires of the Kakiemon Kiln were first started early in the Edo period. Since then, an unbroken succession of artists has inherited the Kakiemon name, extending to the fifteenth-generation member who is active today. Historically, the most famous is Kakiemon I (1596-1666). A document passed down in the Sakaida family, “Aka-e hajimari no oboe” (the record of the origin of Aka-e), describes the achievement, after considerable effort, of producing “Aka-e” (porcelain with overglaze enamels) by Kakiemon I in about 1647. And in fact recent archaeological studies have established that the porcelain with overglaze enamels began to be produced in Arita during the 1640s.

The first Japanese porcelain was produced in the 1610s in Arita, beginning with blue-and-white porcelain and celadon wares. Porcelain production at Arita was further boosted when new techniques that added colors were mastered, and from the end of the 1650s the Dutch East India Company began exporting these wares to Europe. The commercial operations of the kiln began in response to the resulting demand, with repeat orders specifying the highest quality porcelain. Consistently, it was the Kakiemon Kiln that supplied porcelain with colored overglaze that satisfied the most exacting standards.

▼Jump to special section “The allure of Kakiemon-style porcelain for Europeans”

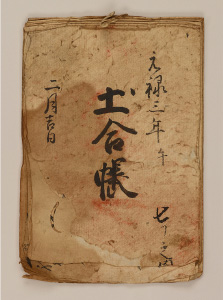

The flourishing years of Kakiemon IV (1641-1679) and Kakiemon V (1660-1691) can be considered as the golden age of the Kakiemon Kiln. Kakiemon V, before his life was ended prematurely at the age of 31, left seven private instructions to his heir, who became Kakiemon VI at one year of age. One of the documents, entitled “Clay Mixing Diary” describes the sources and mixing of raw materials, and includes the statement “when the resulting fired article gives a completely milky-white background, this is truly nigoshide.”

However, sometime during the life of Kakiemon VI, the popularity of Kakiemon-style porcelain having ended, and the Kakiemon Kiln having switched to firing kinrande (gold brocade-style) works, the production of nigoshide came to an end.

Europeans of the 17th and 18th century treasured porcelain brought from exotic lands in the east as a kind of “white gold.” Almost without exception, royalty and aristocrats throughout Europe purchased porcelain figurines to decorate their palaces, castles and mansions, and dined from porcelain dinnerware daily. The porcelain seen as being of the highest quality were the Kakiemon-style pieces that were especially popular during the late 17th century. This was the era of William III, Stadtholder of Holland, which held hegemony over the world’s oceans, and King of England, which he ruled with his wife Queen Mary II—both monarchs were keenly aware of Kakiemon porcelain and were known to have spread its popularity to other areas of Europe. In particular, because Kakiemon porcelain took the courts of Holland and England by storm, countless Kakiemon works have been handed down in manor houses of the aristocrats of both countries.

One of the most famous collections is that of Burghley House, built by Elizabeth I’s trusted advisor William Cecil, and inherited by his descendants, the Earls and the Marquesses of Exeter. The collection includes both Kakiemon plates, bowls, and cups for the dining room, as well as a superb set of figurines (including a sumo wrestler, dog, and rooster). The Kakiemon porcelain placed on the pyramid-shaped shelves of the chimney tree over the fireplace in one of the rooms of Burghley House represent the way that such works of art were displayed in the 17th century.

Augustus the Strong of Saxony, who assembled the collection in the palace of Dresden, Germany, issued an order to create imitations of Kakiemon porcelain, which lead to the establishment of Meissen porcelain as the first porcelain industry in Europe at the beginning of the 18th century. Subsequently, many imitations of Kakiemon works were produced at Chelsea and Derby in England, and in Chantilly in France. In the 19th century, as research into art and aesthetics spread throughout the world, the Europeans learned of the name “Kakiemon” from Japan, and overglaze enamel porcelain, which had enjoyed tremendous popularity until the 18th century, was recognized as being “Kakiemon-style porcelain.”

▲Return to main text.